by Filip Rambousek

On the 30th of October, the EU has gone through with its promise to temporarily lift sanctions against Belarus. More specifically, the EU will for four months raise its travel ban on 170 individuals, as well as its asset freeze of three entities in Belarus.

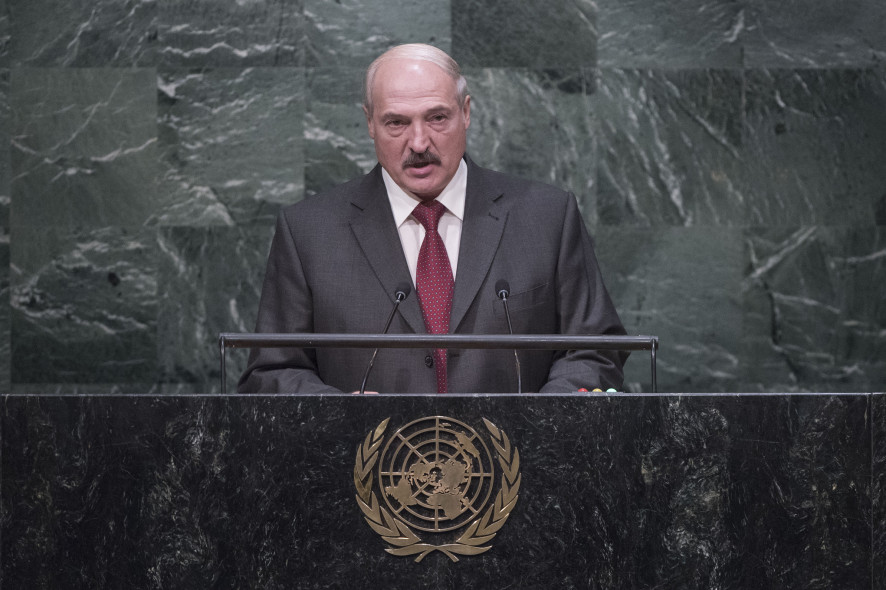

The promise to raise these sanctions was a carrot dangled in front of Lukashenko before the recent elections. In exchange, Lukashenko had to respond with some degree of liberalisation of his regime.

In concrete terms, the EU demanded slightly more democratic elections, and a release of some political prisoners. Lukashenko made good on both expectations. In August, he released six political prisoners. Before the elections, he allowed the only opposition candidate, Tatsiana Karatkevich, to be interviewed by the main government newspaper. During the elections, the OSCE’s observes were met with fewer obstacles to carry out their work than previously. Overall, the OSCE cited “positive developments” in the Belarusian electoral process.

Still, Lukashenko has not suddenly become a dedicated democrat. The political prisoners, while physically out of jail, remain under close government supervision, with many of their civil liberties curtailed. Despite the improvements, we also cannot speak about democratic elections in Belarus. Belarusian civil society representatives complained about non-transparent vote counting. The OSCE’s head observer agreed, stating that “it is clear that Belarus still has a long way to go towards fulfilling its democratic commitments”.

But why should an authoritarian like Lukashenko, after 21 years in charge, and who even without the rigging of votes has the genuine support of around 60% of Belarusians, bother with pleasing the West? The answer is simple: Europe has changed, and its last dictator with it. In fact, Lukashenko has long lost the right to this moniker. This title has been, yet again, rightfully claimed by the leader of Russia. Putin’s regime, with its domestic repression and foreign aggression, currently represents the biggest threat to the EU, as well as the global order. In reality, he is now one of the “better” dictators in the authoritarian pantheon.

Lukashenko is a shrewd, cold pragmatist, whose only goal is to stay in power. He is very well aware of the threat that the new doctrine of Putinism presents to his position in Belarus. With his invasion of Ukraine, Putin has declared that he has the right to get involved in the internal affairs of any country with a Russian minority. Because of this, Belarus is obviously a prime candidate for the Russian army’s next trip abroad. To Lukashenko, a slight liberalisation of the regime represents a lesser evil, and a lesser threat to his power, than a further deterioration of his relations with the West and total dependency on Russia.

Lukashenko is therefore doing all he can to reinforce Belarusian independence. His concerns were well illustrated in the elections’ propaganda campaign. While in the past, government posters emphasised economic progress and social stability, this year, the billboards boasted Belarusian soldiers, with slogans such as “Standing on the Guard of Belarusian Independence”. More importantly, Lukashenko has recently rejected Russian designs at a new army base in Belarus, retorting, rather prosaically, that Belarus “doesn’t need it”.

This geopolitical shift is also reflected in the sudden thaw in the relations between the EU and Belarus. While the support of the respect of human rights abroad is an important aspect of EU’s foreign policy, Lukashenko has not done enough to deserve this immediate change of European attitude towards his country. Rather Lukashenko has played his cards well, and managed to place himself in a position wherein he is at the same time universally disliked and yet indispensable. According to Radio Free Europe’s Brian Whitmore,

At home, he has turned himself into a bulwark against domination by Moscow. For Moscow, he’s turned himself into a last line of defence against a pro-Western Coloured Revolution in Belarus. For the West, he has made himself useful as a counterweight to Moscow.

This thaw may, therefore, actually be a rare example of pragmatism, strategy, and long-sightedness in the EU’s foreign policy. The removal of sanctions is a concrete concession, designed to bring Putin’s erstwhile vassal closer to the EU’s sphere of influence. For once, it seems, the EU has decided to seize the day.

It has made a good first step, and should continue in this strategy. It should support Lukashenko’s every liberalising step, and offer concrete financial and other rewards in exchange. In this way, Belarus would decrease its dependency on Russia further. At the same time, the EU should keep pushing for increased respect for human rights, and threaten Lukashenko with an immediate and stricter imposition of sanctions, should he backtrack.

This will have the effect of isolating Russia, but it will not change Belarus. It is crucial to keep in mind that in Belarus Lukashenko holds genuine, overwhelming support of the population. If the EU also aims at promoting human rights and democratic principles, therefore, the education of the younger generation of Belarusians is the only way of shifting the country westwards. The EU should support, with financial and political means, the efforts of Belarusian civil society, independent media and NGOs. There are some interesting projects going on such as Dutch-Polish Russian language TV project, which is designed to counter Russian propaganda. This has high potential, since most Belarusians get their information precisely from Russian language TV.

These are long term plans. For now, we should support any country, and any dictator, who has made even a symbolical gesture at a departure from Putin’s inner circle.

Image by United Nations Photo, taken from flickr