The recent Dutch election results are currently celebrated as a sign of hope for pro-European voices and a moment of glory for democracy in Europe. One group that claims to have made a contribution to the defeat of populism in the Netherlands is the movement #Pulse of Europe. Supporters demonstrated on public squares across Europe to the Dutch slogan ‘blijf bbij ons’ – stay with us.

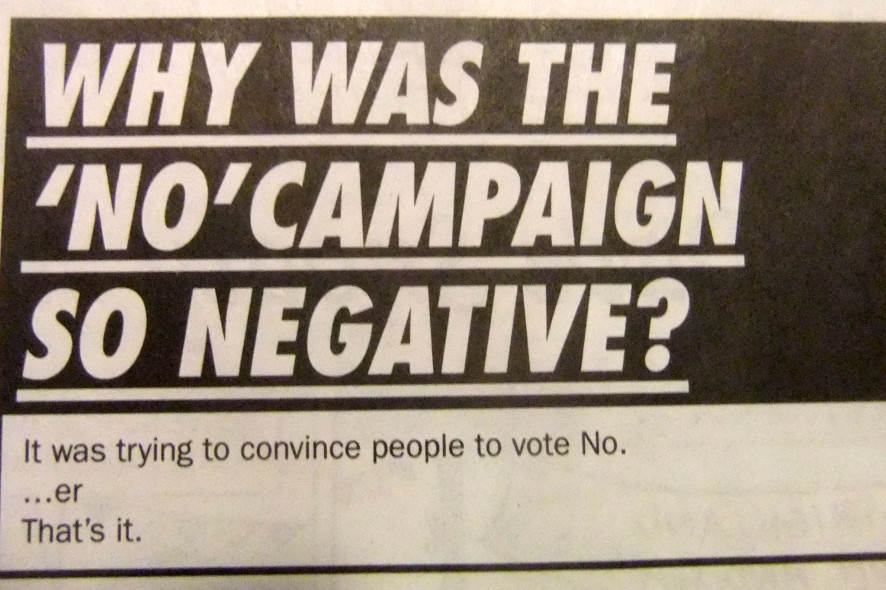

Over the course of the past weeks, this protest movement has increasingly been covered by the media. In recent years, street protests across Europe have been anti-European, anti-immigration, anti-austerity or anti-Trump protests. Yet Pulse of Europe is different. It is not directed against something – but for. Last weekend the new civil movement has again managed to rally thousands of people across Europe – yet foremost in German cities – on the street. Their common cause: demonstrating for Europe, notably to display an optimistic spirit and a positive atmosphere of hope. An atmosphere that was further fueled by the recent election results in the Netherlands. Under the umbrella of Pulse of Europe people have now gathered every Sunday since eight consecutive weeks in various city centers across the continent to demonstrate for Europe and the EU.

But what does this movement actually stand for and what do its supporters aim for? The origins can be traced in the German city of Frankfurt – which could be considered at the “pulse of Europe” by means of its central geographic location and as the siege of the European Central Bank. Pulse of Europe officially proclaims its’ objectives on its website: to contribute to the persistence of a united democratic Europe that is based on values such as respect for human rights and freedom of speech, a Europe which “secures peace and guarantees individual freedom, justice and legal security”. Shocked by the success of right-wing populists in the UK and the US and the surge of populist parties in Europe, its supporters aim to show that “the majority of people believe in the fundamental idea of the European Union, its reformability and development and does not want to sacrifice it to nationalist tendencies”. Due to the fact that the public debate is often dominated by „destructive”, anti-European-voices, those that still believe in a common European future should stand up and become more visible.

Dutch election results as a first victory

Certainly, Pulse of Europe incarnates the hope to wake up European societies and create a pro-European momentum against the backdrop of national elections in major EU member states. The Dutch election results were among the hottest topics for discussion between protesters in Germany. One of the lead organizers of one of the events argued on stage that the fact that Geert Wilders did not win the Dutch election was also due to the influence of Pulse of Europe. People in the Netherlands would have seen the protests, for example in a video on Facebook with the title ‘blijf bij ons’ , which has been watched more than 35.000 times. While the spectre of a PVV-led government is off the agenda for the moment being, populism is still prevailing throughout Europe. When French voters hit the ballot boxes in about a month’s time from now, the biggest fear of a pro-European citizen is a victory of the Front National which would at best alienate one of the EU’s founding members and at worst lead to a Frexit and the threat to the very existence of the Union.

On March 25th Europe’s heart rate will accelerate

In Cologne/Germany, more than 1000 people gathered at the local pulse of Europe demonstration last Sunday. Demonstrators could be heard speaking German, French and English. Speeches from people of different origin were held on stage and a Ukrainian woman reminded the crowd that people in Kiev have paid with their life(s), demonstrating for the same European values as the people present in Berlin or Strasbourg. The following protest march was very slow and more of a Sunday-walk with the family than a hectic outburst of anger. Only very few people were yelling one of the previously distributed protest chants and crowds of children which had been brought along by their parents were playing with soap bubbles. The atmosphere was calm but pleasant as people were talking. This is how it looks like, a moment of European identity. Next weekend, on the 25th of March Europe will celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome. The treaty is often described as the birth certificate of the EU. This weekend the pro-European protest movement will very likely reach a new peak, although other protest movements such as the March for Europe might lead to a more uncoordinated distribution of potential demonstrators. Either way, on this day Europeans will be visible.

What is the real potential of the movement?

Men and women of every age group were present in Cologne, but one could see that the majority of the people were white and in their mid-thirties/forties. By their style of clothing, the overwhelming majority could be identified as middleclass or upper middleclass people. Frankly, the demonstrators were exactly those people that benefit the most from the EU. As an eye witness one could not help but being reminded that the EU is often described as a neoliberal project of the elites. The people present were all beneficiaries of the neoliberal capitalism that is an inherent part of the EU as an economic project. It is a project that has no mandate for social policies and has less to offer to people that are left behind in such a type of economy. Liberal European values are worthy to celebrate, but the European Union is very far from being perfect.

The EU needs to come up quickly with answers if the crowd is to look different and more colorful on future occasions. One answer could be a Union that becomes active in the field of social security and that stands up for a fair distribution of wealth, an EU that emphasizes its basic principle of solidarity. Arguably, for such an EU many people would go on the street. Such an EU – strong and united – could safeguard peace, prosperity and liberal values. It could shape the globalized world of today and tomorrow, so that no one in Europe feels left behind. Certainly, it would do better than any national state in the face of powerful tax evading multinational corporations or superpowers like China. This might be the real potential of Pulse of Europe: to revitalize European solidarity and to give the EU the mandate it needs to become a Union which everyone would be willing to support on the street.

“In 2045 our grandchildren should celebrate 100 years of peace in Europe”

The upcoming weekend is indeed a moment to celebrate and to show support for the European values. Europeans reject an overly bureaucratic Brussels administration yet they crave for a free open society that is based on liberal values, prosperity, free movement of people, goods and services and foremost peace on the European continent. Why not join the movement (yourself)? Pulse of Europe pursues noble goals that are worth considering, especially when looking ahead to the future. One demonstrator’s sign read as follows: “In 2045 our grandchildren should celebrate 100 years of peace in Europe”. This peace seems to be endangered by the current surge of right wing populism. Resistance is imperative if the success of populism is to be curbed in favour of a united Europe. Geert Wilders has not won a majority in the Dutch election, but he still captured the second most votes of all parties. If not winning the election, he managed to shape the public debate, triggering the winning party VVD to adopt increasingly conservative lines.

The political struggle in Europe continues. Arguably the strongest argument to defuse the claims of right-wing populist comes from one of the populists’ own myths: When movements like Pulse of Europe rally thousands of people for the European cause, populist demagogues will have a hard time presenting themselves as the voice of the majority. To prove the demagogues wrong and to prevent uninformed decisions such as the Brexit to happen again, people should consider going for a nice spring-walk to their city center next weekend. And thereby contribute to the future of our continent. Democracy has been suffering long enough from lazy democrats. Therefore this article ends with the famous call of Stephané Hessel: Indignez-vous! Time for outrage! and feel the pulse of Europe.