by Cristian Mihai Lazăr.

In the last year Romania has inarguably found itself in a most decisive period for its future as a state. The importance derives from the internal politics that are outlined especially after the last elections, the parliamentary elections on December 11. Roughly one year after the protests that followed the tragedy of the Colectiv club (which resulted in 64 deaths), the protests which swept down a political government and consequently led to the establishment of a technocratic government, both for the legislature and the executive, it was now imperative the regain the political and popular legitimacy. This could not have been achieved in any other way except through the prism of democratic elections.

The campaign for this year’s legislative election was dull, lifeless and did not generate any collective emotions. Of course, the candidates were mainly responsible for this situation, but also a new electoral law was among the reasons as well – a law that is very rigid regarding the operations and financial expenses that can be conducted during the campaign. In comparison, ‘on the other side of the coin’ are the campaigns that are conducted in the USA, which are characterized by huge campaign budgets and popular entertainment aspects. Besides the two traditional political parties PSD (Social Democratic Party) and PNL (National Liberal Party) in competition for the confidence of voters, not even the new political parties (most of them having old personalities) managed to attract a substantial number of Romanians to vote. Speaking about the categories of voters: on the 11th of December the young people, unlike in the presidential elections when there was a massive presence of the youth which made the difference in the final outcome, this time they remained indifferent and less willing to vote. With a lack of a collective emotion and surprises, the elections confirmed what was already outlined: a predictable victory for the left wing. Nevertheless, the proportions were surprising.

After the political left lost the power last year in consequence to the public revolt which swept down the social-democratic Prime Minister, the PSD and the left wing parties secured a crushing victory receiving 45.47% of the total votes. We can observe that the victory of the Romanian political left wing was in accordance with the trend that already had formed in the East and South of Romania (as well as in both the Republic of Moldavia and in Bulgaria the left wing parties have achieved victory in last month’s elections). We can speak about a remarkable comeback, after the consequences of last year’s protests when the confidence in the party has decreased incredibly and the former Prime Minister, Victor Ponta, became prosecuted for corruption (an accusation which he denied). Nonetheless, the withdrawal from the government a year ago and the appointment of a cabinet of technocrats were a political-saving solution. In this way, the PSD basically managed to be at the same time in opposition and in government, keeping the key positions in the state both at local and central levels. Permanently, the socialists showed themselves hostile to the technocratic government, blocking any measure or attempt to reform a politicized administration. The “triumphing march” of these elections was also assured by the demagogic voracity and populist irresponsibility seen in some parts of the promoted government program. In brief, if the PSD program becomes reality, Romania would witness salary and pension increases, the elimination of half of existing taxes, a gigantic hospital built in the capital of Romania, new regional hospitals and no less than five new highways (it was not said when will it happen though, we shall see).

Managing this election victory won´t be easy, especially because the problem of this party will be to nominate a Prime Minister who can carry out this political program. The first option seems to be the current leader of the party, Liviu Dragnea – who is now being sentenced to 2 years of suspended prison for electoral fraud. However, the Romanian law does not allow the appointment of a convicted person into the government. The most recent political movements are showing that Liviu Dragnea has succumbed to pressures of the law enforcement and Sevil Shhaideh will probably represent PSD`s nominee and thus the future Head of Romanian Government. About Sevil Shhaideh, it is known that she is one of the closes political friends of Liviu Dragnea. In any way, in confrontation between the popular will and the rule of law, Romania cannot afford another political crisis at this moment. In these outlined circumstances it remains to be seen how the political hegemony of the PSD will evolve.

At the opposite side of this triumph we can notice the great failure of the main opposition, the National Liberal Party. As a consequence to the election outcome, the president of the party resigned the day after the elections. The problems of the party were not acute, but rather chronic. The symptoms of the defeat were also visible at local elections, where the results were far below expectations. The failure was generated by a lack of vision, and the lack of vision was generated by a lack of leadership. It may even be said that the PNL has participated at these elections without leaders. The message they promoted lacked substance and was more focused on the possible damage of a PSD victory. However, there seemed to be a few positive signs as well as the party came up with new candidates, promoting many young people and a fresher elite in different policy areas. The reforming of the party is relevant not only for its own salvation as a political party but also to provide Romania with a powerful right-wing in its politics spectrum to assure a viable balance of the political powers. They need to get rid of the tired portraits and adopt a persuasive, combatant, and articulated speech. The National Liberal Party must become again liberal more than ever.

The astonishing item of the elections was the appointment in the Parliament of the USR (Save Romania Union) party with a redoubtable score of 8.87% of the votes for a party which is less than one year old. This party managed to win the confidence of Romanians that are unsatisfied with the “system” and with the current political class. Lacking experience and based on criticism so far, this young political party emerged as the third force in the new Parliament, despite limited resources and logistics. More than ever, they will need an offensive energy, strength, and most of all in order to assure their existence in politics, they must find an ideological identity.

The former president of Romania, Trăian Băsescu, has claimed himself to be the main opposition for the future left wing Cabinet along with the Popular Movement Party whose leader he is. This is a new party, participating in its first parliamentary elections and becoming part of the new legislature by passing the electoral threshold. In order to ensure a sustainable coalition, PSD will also be supported by ALDE, a party which is led by the former liberal Prime Minister C. P. Tariceanu. The Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania, a party of minorities, is the other party that managed to be appointed in the Parliament and it has great chances to form too a coalition with PSD and be in government together. As a positive item, unlike in many European cases, fortunately the current nationalist-xenophobic voices did not win the confidence of voters and failed to be appointed into Parliament these elections.

In the 11th of December the voters have expressed themselves in a categorical way. As in any democracy, the majority speaks and the manifested option cannot be contested. Its implications will be major. During this mandate, in 2019, Romania will be one of the countries to hold the presidency of the EU Council. Thus, another reason why the votes of Romanians given on the 11th of December will weigh a lot more, influencing both the national and European political spectrum.

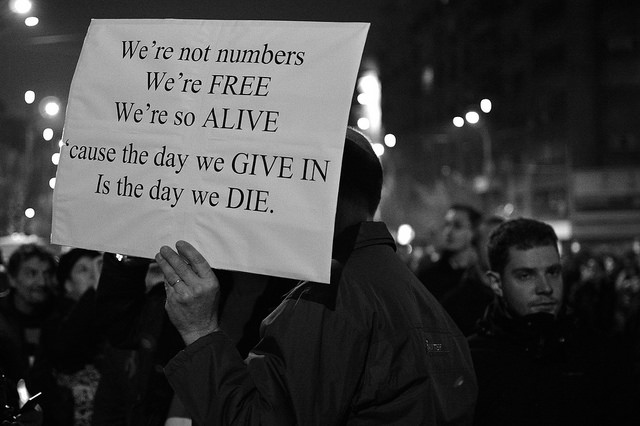

Image by Janrito Karamazov, taken from photopin