Since the Brexit vote in the UK there has been a lot of speculation concerning the next countries to leave the European Union. France is being repeatedly named in those lists. There are several reasons why France is not likely to leave the EU any time soon.

While British politicians are fairly unpopular in Brussels, French MEPs make up the core of the political groups and their messages, especially those who have pushed political integration and centralization. Joining the EU bureaucracy is considered to be a capstone to a successful political career, and a chance to be considered a “real” statesmen.The French political class is quite committed to the EU project.

Moreover, there is substantial evidence that the French population overall has a relatively high opinion of the EU and its institutions. Polling conducted after the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom backs this up: in a Paris-Match/iTELE poll in June of this year, only 35% of the surveyed people supported the idea of France leaving the European Union. A similar TNS poll only found 33% supporting the same. This trend is also confirmed by the current lead and importance of 2017 presidential candidate Alain Juppé, a former prime minister, running on the platform of being “a European” while favoring political integration in the EU. The pro-EU Juppé is the current leader of the field in his primary with 42% (with only 28% going to his chief rival, former president Nicolas Sarkozy), and therefore the most likely to become the next president.

The French May Be More Easily Bullied than the British

The Brexit reactions from EU officials only prove what the general trend of the European Union is: join our club or we will bully you. After creating a single market and restricting trade policies of its members, the EU then forces those who do not give in to accept all the edicts of the European commission — or else. If some sectors of the French population begin to push for separation, the EU will again get the fear machine rolling to prevent other countries from leaving.

This can be seen in the very language used by the pro-EU side, and leaving the EU is routinely described as “leaving Europe” as if being in the EU is synonymous with being European. Obviously, Europe as a continent (physical) is quite different from the European Union (political), but equating the two makes every potentially defecting country feel the effect of physically drifting away. It’s the playground bully telling his friends not to play with one particular kid so that he obeys the rules.

Perhaps the biggest factor in applying pressure against separatists is the press. While the British press has been, to put it quite frankly, enormously critical of the EU at times, the French press doesn’t feel this need at all. In the UK, the press pushes the parties, in France the parties push the press. News sources are either state-run or affiliated to one of the two main parties, of which both praise the European Union above all else.

In the aftermath of the Brexit vote, the editorial of the major newspaper Le Monde wrote: “We believe … that ‘Brexit’ will release some of the darkest forces working European views today: regressive nationalism, a rise in far-right protests, and — here and there — threats to democracy.” Le Monde’s conservative rival publisher Le Figaro expressed its worries that the UK vote would trigger a referendum in France: “The risk is great as other countries rush into the breach opened by the United Kingdom.” The left-wing Libération seemed content with the result, because the UK had been in the way of further integration, of a ‘common project.’ Les Echos started the day by titling that the day of the referendum would remain “a black day for Europe.” (Source) The state-broadcaster France Télévision was visibly in shock, then followed its own anti-Brexit agenda for weeks by showing the “plummeting British stock market.” The influential political radio station Europe 1 blasted the Brexit vote by inviting (of all people) Tony Blair on the air, reassuring listeners that “it is possible to find a deal for the UK to remain part of the European Union.”

France’s Earlier Referendum

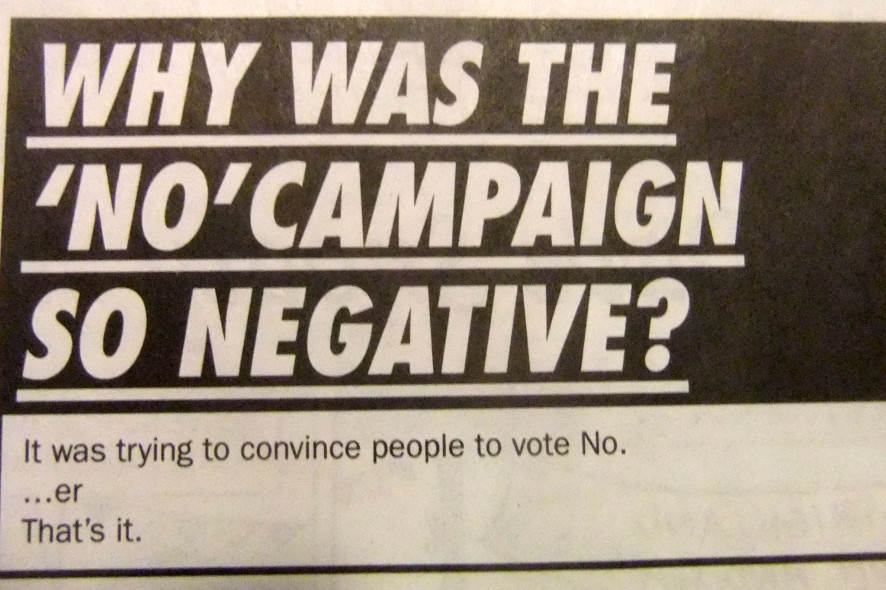

In 2005 the French electorate said “No” to the EU constitution. The reason for that was that French voters feared that the EU would impose “a neoliberal economic model” and reduce the standards of social security in the member states. In response, then-president Nicolas Sarkozy teamed with other European leaders a backroom deal called the Treaty of Lisbon, but made it quite clear that there would not be a vote on this new treaty at all. The Dutch and French failures to pass treaties through the referenda process taught the EU a lesson: referenda shouldn’t be allowed.

The EU is Insurance for the French Regime

This is by far the most important part of this argument that absolutely needs to be made: France was a strong voice for solidarity in the Irish and Greek bailouts, with support from the public, because the EU and its central bank will be France’s best insurance policy in the next crisis.

French politicians have learned from the legacy of François Mitterrand. In the early years of his administration, Mitterrand set to work implementing a variety of hard-left policies. These policies so crippled the French economy that Mitterrand was forced to take a hard pro-market turn just a few years later. Many French politicians today still believe Mitterrand compromised far too much.

For this new breed of pro-EU leftist politicians, the strategy is clear: it’s full speed ahead. No reforms, no apologies. Should hard left policies appear to fail this time around, well, the European Central Bank can just step in. Since the European Central Bank must deal with the consequences of France’s drain on the euro, the rest of the continent will have to bailout the République, where even outside of a crisis, the French debt level is among the highest in Europe at almost 100% of GDP.